The Warm Winter Flower

With a name like “skunk cabbage,” Symplocarpus foetidus might put you off. The common name isn’t wrong; the flowers of this arum plant are smelly.

But what this plant should be known for is its incredible ability to produce its own heat in a metabolic process called “thermogenesis.” This process, similar to how warm-blooded animals burn internal energy to produce heat, completely flips the script on the dictates of winter. I found these flowers blooming in the second week of January.

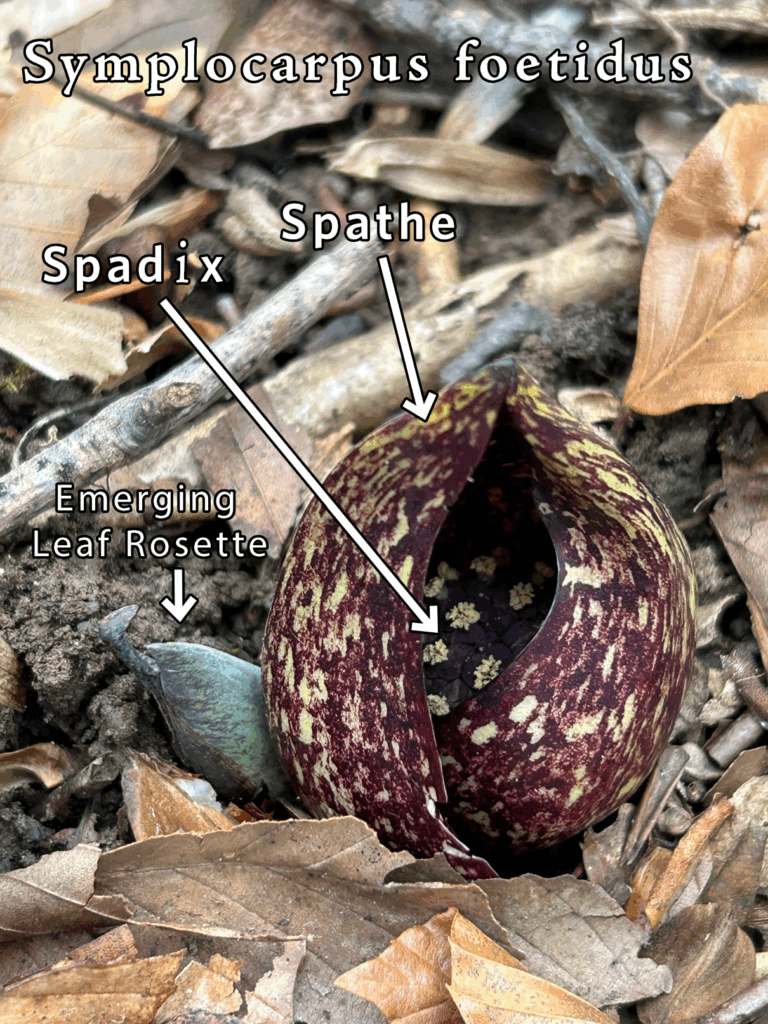

Using thermogenesis, the skunk cabbage generates its own heat and regulates it, burning the energy stored in its roots, even melting the snow around itself, to maintain a toasty 15°C – 30°C (59°F – 73°F) within the plant’s spadix. The “spadix” is the rounded cluster, the inflorescence of petal-less flowers within the protective mottled hood, called the “spathe.” This is the part of the plant you may see early in the year if you search along creeks in wet forested areas of the Eastern US.

The form of this plant is characteristic of those in the Arum family, like peace lilies and jack-in-the-pulpits. The spadix/spathe structure on the skunk cabbage acts as a heating tent for its blossoms and the insects that come to pollinate them (which include flies, bees, and beetles.) The heat also helps disperse the stinky smell that attracts these pollinators.

When the outside temperatures get above freezing, the skunk cabbage sprouts and unfurls its leaves in a large rosette, resembling cabbage. The leaves absorb whatever sunlight they can before the forest canopy overhead fills in and darkens the forest floor. The skunk cabbage might have a few months to fill up its thermogenesis reserves. By summer, the leaves, so quick to grow, may already be wilted and breaking down.

By then, the flower of the plant will have long since withered away. If pollination was successful, the spadix will develop a bumpy complex of fruits that drop their seeds in the mud in late summer.

The roots are no less interesting. They are contractile, pulling the plant’s rhizomatous stem into the earth a little every year. They are thick and fibrous, resembling a mop head, stretching into the mud to anchor the plant and keep safe its winter energy reserves.

Skunk Cabbage, with all its adaptations to thriving in the cold, is the king of early starts. The ice and snow cannot keep it from growing its weird and wonderful winter flower. I encourage everyone when they visit the preserve to seek out this plant along the creeks while it’s still showing off its warm, smelly bloom!

Read More:

https://sites.tufts.edu/pollinators/2020/02/turning-up-the-heat-strange-and-stinky-skunk-cabbage/

https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/plant-of-the-week/symplocarpus_foetidus.shtml

https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/the-first-blooms-bring-the-heat

https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/skunk-cabbage-symplocarpus-foetidus/

Here is a scholarly article if you want an in-depth look at how

the plant thermoregulates:

Haruka Tanimoto, Yui Umekawa, Hideyuki Takahashi, Kota Goto,

Kikukatsu Ito, Gene expression and metabolite levels converge in the

thermogenic spadix of skunk cabbage, Plant Physiology, Volume 195,

Issue 2, June 2024, Pages 1561–1585, https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiae059